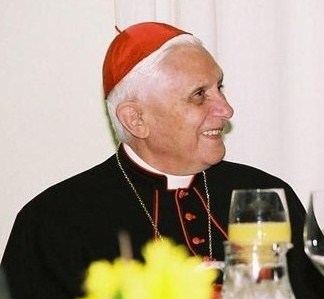

Newly elected Pope Benedict XVI

The Mind of Benedict XVI

By

Father D. Vincent Twomey, SVD

The publication of Dominus Iesus, in August 2000, caused worldwide outrage. The document — issued by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), headed by then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger — affirmed the absolute claims of Christianity and the Catholic Church vis-à-vis the other religions. In his book, Truth and Tolerance (German, 2003; American, 2004), Cardinal Ratzinger offered a 284-page answer to the outrage. In the preface, he wrote: "As I looked through my lectures on [Christian belief and world religions] over the past decade, it emerged that these approaches amounted to something like a single whole — quite fragmentary and unfinished, of course, but, as a contribution to a major theme that affects us all, perhaps not entirely unhelpful." These sentiments reveal not only the dominant characteristic of the man — his humility and courage — but the nature of most of his writings.

Ratzinger is acutely conscious of the fragmentary nature of all he has written, but he makes a virtue out of this weakness, which is caused by the simple fact that he was called to sacrifice his preferred life as an academic to serve the Church, first as Archbishop of Munich, then as Prefect for the CDF, and now, of course, as Pope Benedict XVI. As he says in one of his most recent publications, Values in a Time of Upheaval: How to Survive the Challenges of the Future (German & American, 2005), "perhaps the unfinished character of these attempts can help to advance thinking about them." All his writings are contributions to an ongoing debate, first in his own discipline — theology — and later, as he became more a pastor than a scholar, in the public debate about the future of society and the Church's role in it. And despite their fragmentary nature, his writings do "amount to something like a single whole." Joseph Ratzinger is not simply a recognized scholar of the highest quality. He is an original thinker. The result is an inner consistency that marks all his writings, though each piece never fails to surprise with its freshness, originality, and depth.

Augustine or Modernity

From the beginning of his own studies, Ratzinger and his contemporaries in Munich tended to seek an alternative to Neo-Scholasticism, the dominant system of Catholic theology at the time. Neo-Scholasticism was an attempt in the 19th and early 20th centuries to recreate the philosophical and theological "system" of St. Thomas Aquinas. Ratzinger, instead, turned to the great thinkers of the early Church. For his doctoral thesis, he studied the Father of the Western Church —and of Western civilization — St. Augustine. His topic was Augustine's understanding of the Church and thus, by implication, his understanding of the State and the political significance of Christianity. His dissertation, People of God and God's House in Augustine's Doctrine of the Church (German, 1954), is a classic. It is also the root of much of his later theology.

His postdoctoral dissertation (Habilitationsschrift) was devoted to Thomas Aquinas's contemporary, St. Bonaventure, who was also very much in the Augustinian tradition. It is an analysis of the attempt by the great Franciscan theologian to come to terms with the new understanding of history conceived by the Abbot Joachim of Fiore. Eric Voegelin argued that the speculations of Joachim of Fiore are in large part the source of modernity; they helped replace the Augustinian concept of history that had formed Western Christendom. Ratzinger was not a confirmed Voegelinian — he quotes Voegelin in only one of his early writings — but it is interesting to see how the two men reached similar conclusions from quite different starting points.

In Augustine's view, history is transitory, and empires pass away; only the eternal Civitas Dei (the "citizenry of God," as Ratzinger translates it) lasts forever. Its sacramental expression is the Church, understood as humanity in the process of redemption. By contrast, Joachim proposed a radically new understanding of world history as a divine progression of three distinct eras, the last being the era of the Holy Spirit when all structures (Church and State) would give way to the perfect society of autonomous men moved only from within by the Spirit. This understanding of history amounts to what Voegelin called "the immanentization of the eschaton." It rests on the assumption that the end of history is immanent in history itself — the product of its own inner movement towards ever greater perfection, towards the kingdom of God on earth. This idea is at the root of what we mean today by "progress." It underpins, albeit in different ways, both radical socialism and liberal capitalism. And it has had a profound effect on political life, giving rise to both revolution and secularism.

Bonaventure, according to Ratzinger, failed in his critique of this progressive theology. But Ratzinger's study of Bonaventure alerted him to the philosophical and theological issues underlying contemporary political life. This is seen, in particular, in his later treatment of the radical forms of liberation theology, based on a Marxist notion of history with its roots in Joachim of Fiore.

Early Writings

It is difficult to give an overview of Ratzinger's publications considering their range, the fragmentary nature of most of them, and their sheer volume — some 86 books, 471 articles and prefaces, and 32 other contributions (according to the latest list compiled in February 2002), averaging about 30 (at times, very brief) entries a year in recent years, not counting official documents issued by his Congregation. What follows must be restricted to some of his more representative scholarly writings.

As a professional academic in Freising and Bonn, his early writings were devoted to the basic principles and presuppositions of theology. He stressed the affinity between reason and revelation (and so the Church's appreciation of philosophy as an ally in its enlightened critique of mythological religions). Reason for Ratzinger is our capacity for truth (and so for God). Like language, reason is at the same time both personal and communal, as indeed is revelation, the social dimension of which is found in the Church. His entire theological opus is rooted in Scripture, the ultimate but not the only norm of all theology. Although he judiciously uses the findings of modern critical scholarship, he goes beyond them in the spirit of the Church Fathers, whose interpretation of Scripture is based on the unity of the Old and New Testament (the latter being the fulfillment of the former) and the unfolding of Tradition under the direction of the Holy Spirit.

The early period was greatly influenced by the Second Vatican Council and its aftermath. Ratzinger, a peritus or expert advisor to the Council, published several commentaries on texts issued by the Council as well as personal reflections on it and its aftermath. Dealing with the vexed question of the universal nature of salvation and the particular nature of the Church, which the Council had posed with renewed sharpness, he developed his understanding of salvation in terms of Stellvertretung (representation or substitution): just as the incarnate Word of God gave his life "for the many," so too individual Christians live not for themselves but for others, while the Church exists not for itself but for the rest of humanity. His major writings in this area include Revelation and Tradition (with Karl Rahner, 1965), The New People of God (German, 1969), and the Principles of Catholic Theology (German, 1982; American, 1987), perhaps his most important academic writing. He would later return to these early fundamental theological concerns in such books as The Nature and Mission of Theology (German, 1993; American, 1995) and Called to Communion (German & American, 1991).

Doctrine of the Faith

In his middle period (at Münster, Tübingen, and Regensburg), Ratzinger produced his most famous book: Introduction to Christianity (German, 1968, revised, 2000; American, 1969), translated into some 19 languages, including Arabic and Chinese. Originally a series of public lectures on the faith, which Ratzinger gave in the summer term of 1967 for students of all faculties of the University of Tübingen, it opens with a masterly attempt to situate the question of belief and its communal expression in the modern world before going on to comment on the contents of the Creed. It is one of his many purely theological tracts, which range in topic from creation to eschatology, from the interpretation of Scripture to the principles of fundamental theology, from ecumenism to catechetics and the subject closest to his heart: the Eucharist and the liturgy. These tracts are not simple affirmations of orthodoxy. He approaches every topic by way of the (often unspoken) questions posed by contemporary culture and the state of contemporary theological scholarship.

The most significant book of this middle period is perhaps his Eschatology — Death and Eternal Life (German, 1977), which is a systematically worked out textbook, the aim of which is to overcome the hijacking of eschatology for political purposes and recover its transcendent and personal dimensions. This period is also marked by his growing concern with developments in catechesis — the handing-on of the faith in schools and colleges — as reflected in a talk he gave in France, which caused quite a storm at the time: Mediating Faith and Sources of Faith (German, 1983). This concern prepared him for the day when, as Cardinal Prefect, he chaired the commission set up by Pope John Paul II to oversee the composition of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, one of the most significant achievements of the previous papacy.

As Cardinal Archbishop of Munich and then as Cardinal Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Ratzinger continued to research and publish in academic journals as a private theologian - quite independent of his position as Prefect. These publications were sometimes part of his own homework in preparation for composing the official documents that carry his signature. His publications during this (his third or later) period included various sermons, reflections, and spiritual exercises. All are marked by a deep spirituality, simplicity of language, and beauty of expression, such as To Look on Christ: Exercises in Faith, Hope and Love (German, 1989; American, 1991). His pastoral concern also produced some of his finest writings on the Eucharist and the liturgy, such as The Spirit of the Liturgy (2000), which he wrote during his vacation in Regensburg in the hope that it would give rise to a liturgical renewal like the one sparked by Romano Guardini's similarly titled book in 1918.

In this final period (before his election as Pope), his theological writings tend to be more and more determined by pastoral concerns and later by the various issues that called for an authoritative response from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, such as liberation theology, developments in biotechnology, New Testament attitudes to the Jews, and, most recently, the relationship between Christianity and the world religions, one of the topics he had dealt with in his early formative period as an academic theologian. His mature reflections on the latter topic may be found in Truth and Tolerance, mentioned above.

Theology and Politics

Ratzinger's reflections on morality go back to his middle period (see, e.g., Principles of Moral Theology, German 1975), while his theology of politics can be traced back to his earliest research — his doctoral and post-doctoral theses — and to his first writings as an independent author, such as Christian Brotherhood (German, 1960) and The Unity of the Nations: A Vision of the Fathers of the Church (German, 1971). The latter is fascinating, among other things, for its insights into nationalism's potential evil when it becomes an absolute and its threat to the Church, as first perceived by Origen of Alexandria, the third-century founder of speculative theology. As Archbishop of Munich, Ratzinger's pastoral concerns gave rise to his mature theology of politics, early intimations of which can be found, for example, in the twelve sermons published under the title, Christian Faith and Europe (German, 1981).

A representative selection of his writings on the theology of politics (including an important essay on liberation theology) may be found in Church, Ecumenism, and Politics: New Essays in Ecclesiology (German, 1987; the English translation, 1988, is rather poor and there is even a large passage missing). He describes this collection as "essays in ecclesiology" — politics, like ecumenism, being but an aspect of his theology of the Church. His theology of politics combines a critique of modernity (understood as the attempt to create a perfect society by social engineering as justified by one or another political ideology) with an attempt to delineate the contribution of Christianity to a humane society and to modern democracy. Here conscience or personal moral responsibility plays a key role, as does the recognition (already found in the New Testament) that there is no place for a "political theology" (like liberation theology) and, related to this, that there is no unchanging template for politics (and so no justification for political ideology). Politics is the "art of the possible," the arena of practical reason (of prudence and justice), and so of compromise — albeit within moral parameters that are, in principle, non-negotiable (though today they are hardly recognized as such due to the dominance of rationalism and utilitarianism). Also significant for an appreciation of his political thought is the collection of talks published under the title Turning Point for Europe? (German, 1991; American, 1994) and, above all, Truth, Values, Power: Litmus Tests for a Pluralist Society (German, 1993), which contains his most important contribution to moral theology, namely his understanding of conscience.

In Values in a Time of Upheaval, Ratzinger discusses ways of recovering, in a world roiled by globalization and multiculturalism, a moral consensus that is both objective and universal. In it, he returns to the question of the relationship between faith and reason that was the subject of his inaugural lecture in Bonn in 1959 as a fledgling theologian. Now the topic emerges as an aspect of the challenges posed by the undermining of traditional means of orientation within all societies. Faith and reason, revelation and enlightenment, need each other in order to liberate the potential in each to confront, and help overcome, the dangers that threaten humanity.

Politics and Ethics

Ratzinger's contribution to political and ethical thought is less well known, despite the fact that he was made a member associé étranger in the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques of the Institut de France in 1992 in recognition of his writings and perhaps his public stances in these areas — he replaced the Soviet dissident nuclear physicist, Andrei Sakharov. For more than 40 years, Ratzinger has written extensively in response to social and political developments in Europe and the world. His latest book, The Europe of Benedict in the Crisis of Culture (Italian, 2005), is made up of three papers he read on various occasions dealing with this crisis.

A brief discussion of a chapter in Church, Ecumenism, Politics might suffice for a taste of Ratzinger's theology of politics. It is a classic expression of his thought in this area (despite the inadequate translation), and is entitled, "A Christian Orientation in a Pluralist Democracy?" The question mark is important.

Ratzinger is acutely aware that modern democracy cannot stand on its own but needs other moral resources to maintain itself. He looks at the pluralist democracies of Europe and notes their many weaknesses, particularly their tendency to expect too much from society. This attempt to create a new world that will finally, definitively, be a better world is the greatest threat to democracy itself. Behind this threat is the persistence of the Gnostic dream of establishing the Kingdom of God within history once and for all. "The longing for the absolute in history is the enemy of the good within it." The myth of the creation of a perfect society here on earth engenders revulsion against the imperfections of existing society and can engender anarchy, in the irrational hope that once the present corrupt society has been destroyed, a new and better world will emerge. This is the seedbed of most political terrorism.

Ratzinger distinguishes three interrelated aspects of the threat to democracy. The first is the assumption that perfect justice can be achieved simply by changing the economic, social, and legal structures of society. A "perfect society" of the future would supposedly be a society liberated from all kinds of exploitation and injustice by new structures (in other words, social engineering). In fact, it would "free" the members of society from the continual moral effort needed to achieve justice in society. Such a "liberation" would in effect amount to nothing less than the abdication of personal responsibility and personal freedom. It presupposes perfect tyranny. But "neither reason nor faith ever promises us that there will be a perfect world." To toy with the idea is to encourage a false "enthusiasm bent on anarchy." Today's pluralist democracy, for all its imperfections, allows a certain measure of justice to be achieved within clear limits, and some improvement is always possible. For democracy to continue to develop, it is urgently necessary to acquire again "the courage to accept imperfection" — and to learn to appreciate that human affairs are constantly endangered and so call for constant vigilance. Any moral appeal based on the promise of a perfect society in the future is in fact profoundly immoral — it encourages a flight from morality, from free, human, prudential decisions, toward some form of utopia.

The attempt to make morality with all its shortcomings superfluous by promoting the creation of a perfect society has another root. This is the one-sided concept of reason characteristic of modernity, what Vaclav Havel likewise calls impersonal reason. Anything that cannot be quantified, calculated, or verified by "scientific experimentation" is regarded as irrational, illogical. This amounts to the abolition of morality as such. Human decision-making is reduced to an attempt to balance the foreseen advantages or disadvantages of a proposed course of action. Morality becomes personal preference — and so "law has the ground cut from under its feet." If there is no such thing as objective morality, then the law can no longer be conceived as giving legal protection to that which is intrinsically good and forbidding what is intrinsically wrong; it becomes a mere means for preventing opposing interests from clashing with one another. When moral reason is conceived as basically irrational — merely a matter of subjective preference — law can no longer be referred to as a fundamental image of justice but becomes the mirror of the predominant view of the experts or majority opinion. Since views and opinions in society are subject to constant change — and indeed can be profoundly unjust — it is obvious that justice cannot be achieved in this way. Society and the state can only survive if we succeed in re-establishing a fundamental moral consensus in society.

The third threat to modern democracy embraces and extends the previous two. If people are convinced that all there is to life is what we experience here and now, discontentment and boredom can only increase, with the result that more and more people will look for some kind of escape in a search for "real life" elsewhere. Escapism and various forms of "dropping out" become endemic. "The loss of transcendence evokes the flight to utopia," Ratzinger states categorically. "I am convinced that the destruction of transcendence is the actual amputation of human beings from which all other sicknesses flow. Robbed of their real greatness they can only find escape in illusory hopes." One such illusory hope is the construction of a perfect society in the future, which Marx claimed could only come about if people first abandoned God.

Tendencies of Christianity

The modern state is an imperfect society, not only in the sense that its structures will necessarily be as imperfect as its members, but also in the sense that it needs a source outside itself in order to be able to survive and thrive. The question is: what source? Before recommending Christianity, Ratzinger engages in a self-criticism of Christianity as a historical entity and a political force. As a human phenomenon, Christianity (Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, Anglican) is also subject to the ambiguity of the human condition. In the course of its history, it too has given rise to movements and social tendencies that have unhealthy implications for political life and that cannot be ignored. Ratzinger considers three such tendencies.

The first is to misunderstand Christian hope in either purely otherworldly terms or as something to be looked forward to here on earth. The first error encourages Christians to neglect life in society for the sake of the world beyond. The second is the Gnostic temptation to create the kingdom of God on earth. True Christian hope is the mean between these two extremes. It is the theological virtue that enables Christians to endure injustice patiently and to work unceasingly for justice in this world in anticipation of the Final Judgment beyond: "What you did to the least of these little ones," the Eternal Judge will tell us at the end of time, "you did to me."

The second unhappy Christian tendency is the rejection of justification based on human effort ("merit"), which means that human endeavor is considered to be of little consequence for salvation. The resulting notion of holiness based on grace alone, which is only granted to the "saved," permits no accommodation with those who are not "justified" or "saved." This in turn promotes a black-and-white picture of human society and rules out any compromise, with disastrous results. Since politics is the art of the possible, compromise is essential for political life.

The third tendency is really a danger inherent in the very nature of Christian monotheism, namely the Christian claim to truth, which has more than once led to political intolerance. There is but one God, who revealed himself in Christ. Consequently, Christianity could not fit into the Roman concept of tolerance based on polytheism. The Romans considered the various cults in the empire as religious clubs, each free to organize its own private laws and follow its own gods. But Christianity could not accept such a place in society, because it would reduce Christ to one god among many. Christian belief implied a claim to public recognition comparable to the State's. It also denied the State's claim to absolute obedience. Christianity has from its origins been the adversary of all forms of State totalitarianism. But the claim to ultimate truth can result — and has in the past resulted — in political intolerance once the Church itself becomes a political force. Theocracy is an inherent danger, meaning not simply rule by priests (that has been extremely rare), but the attempt to rule society according to explicit religious beliefs, as today in the case of Islam. Theocracy is thus inimical to the basic understanding of political life found in the New Testament. But it is an ever-present temptation.

The Central Question

The central question, as Ratzinger sees it, is: "How can Christianity become a positive force for the political world without [itself] being turned into a political instrument and without on the other hand grabbing the political world for itself?" His answer again is threefold.

First, from its origins in the life of Christ, Christianity on the whole has refused to see itself as a political entity. One of the three temptations faced by Christ at the beginning of his public ministry was to transform the kingdom of God into a political program. "My kingdom is not of this world," Jesus affirmed. "Give to Caesar what is Caesar's and to God what is God's." Caesar represents the State, the realm of political life, which is the realm of practical reason and human responsibility. According to Ratzinger, the New Testament recognizes an ethos or sphere of political responsibility but rejects a political theology, i.e., a political program to change the world on the basis of revelation. Thus all attempts to establish a perfect society (the kingdom of God on earth) are rejected by the New Testament. The New Testament rejection of justification by one's own effort is likewise a rejection of political theology, which would claim that a perfect society based on justice could be established by human effort alone. Perfect justice is, rather, the work of God in the hearts of those who respond to his love (grace). Justice in society cannot be achieved simply by changing the structures of society. It is, instead, the temporary result of continued imperfect efforts on the part of society's members. To accept this is to acknowledge the imperfection that characterizes our human condition and to accept the need to persevere in one's own moral effort. Such endurance in trying to do what is right, to find the right solution to the practical difficulties that arise from daily life in common, is made possible by grace and the promise of everlasting life and ultimate victory in Christ. "The courage to be reasonable, which is the courage to be imperfect, needs the Christian promise [i.e., the theological virtue of hope] to hold its own ground, to persevere."

Second, Christian faith awakens conscience and thus provides a necessary foundation for the ethos of society. Faith gives practical content and direction to practical reason. It provides the necessary coordinates for practical decision-making. The core of the crisis of modern civilization is the implosion of the profound moral consensus that once marked all the great traditions of humanity, despite their superficial differences. If there is nothing intrinsically right or wrong, conscience can be relegated to the private sphere and law can no longer be regulated by morality. Accordingly, the most urgent task for modern society is to recover morality's meaning and its centrality for society, which is constantly in need of inner renewal. A State can only survive and flourish to the extent that the greater number of its citizens are themselves trying to do what is right and avoid what is wrong— insofar as they are truly trying to act in accordance with their conscience and striving to become virtuous. Thus genuine moral formation, by which one learns how to exercise one's freedom, is essential for the possibility of establishing justice, peace, and order in society. Moreover, it is important to remember that the basic morals of modern Western society are the morals of Christianity, with its roots in Judaism and classical Greek thought. It is the residue of these that, filtered through the Enlightenment, gives modern democracy its internal ethical framework. When the Christian foundations are removed entirely, nothing holds together any more. Reason needs revelation, if it is to remain reasonable — if it is to recognize those limits which define us as human beings.

The final point touches on a most sensitive aspect of the interconnection between Christianity and modern pluralist democracy. Today few will deny Christianity the right to develop its values and way of life alongside other social groups. But this would confine Christianity to the private sphere, just one value system among other, equally valid ones. Not only does this contradict the Christian claim to truth and universal validity, it robs Christianity of its real value to the State, which is that it represents the truth that transcends the State and for that very reason enables the State to function as a human society guided by the conscience of its members.

Thus we have the dilemma. If the Church gives up its claim to universal truth and transcendence, it is unable to give to the State what it needs: the strength of perseverance in the search for what is good and just — as well as the source of its ultimate values. On the other hand, if the State embraces the Christian claim to truth, it can no longer remain pluralist, with the danger that the State loses its own specific identity and autonomy. Achieving a balance between the two sides of this dilemma is the prerequisite for the freedom of the Church and the freedom of the State. Whenever the balance is upset and one side dominates the other, both Church and State suffer the consequences. Christianity is the soil from which the modern State cannot be uprooted without decomposing. The State, Ratzinger insists, must accept that there is a stock of truth, which is not subject to a consensus but rather precedes every consensus and makes it possible for society to govern itself.

The State ought to show its indebtedness in various ways, including the recognition of the validity of the public symbols of Christianity — public feast days, church buildings and public processions, the Crucifix in schools, etc. Yet such public recognition can only be expected, adds Ratzinger, when Christians themselves are convinced of their faith's indispensability, because they are convinced of its ultimate truth.